“We focus on one thing, and people know what that is as soon as they see the name on the door,” Matt Neel says in the last quiet hour before the after-school rush hits Xceleration Sports Performance Labs. For anyone not able to visit Neel in the hill country suburbs west of Austin, Texas, his URL reinforces the message: whybeslow.com

“Acceleration is the most important quality in any sport this side of distance running. Velocity does not come into play that much unless we’re training a sprinter. Athletes have to accelerate many more times than they will approach their peak velocity.”

Neel takes a broad view of acceleration, applying many of the same concepts to training golfers, volleyball players and athletes in a range of throwing and rotational sports. Initiating explosive force by training the body’s movement and harnessing the forces acting upon it binds all those sports. One common application at Xceleration are the first few steps after the snap in American football.

5-10-5 training with the 1080 Sprint

Like many of his peers, Neel accepts that football combines are performance art as much as – perhaps more than – sports performance.

With the combine battery becoming a standardized test for aspiring football players, Neel’s challenge is to train his athletes for what comes after the test – the game – rather than the test itself. The 5-10-5 shuttle is one test where Neel trains his athletes to have maximum transference to game scenarios before sharpening them for the combine.

[av_button_big label=’Must read:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/1080-quantum-acl-rehab/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-1mq02oa’]

ACL rehab with the 1080 Quantum: Overcoming the pitfalls of under-loading

[/av_button_big]

He includes the 1080 Sprint in his 5-10-5 shuttle training, manipulating the direction and application of the load, as well as the magnitude. The athlete wears the 1080 Vest, which has nine attachment points on the front and nine on the back. The 1080 Sprint, then, applies a transverse load to the athlete in addition to a load in the plane of motion. This trains the athlete to maintain body alignment and control their movements against multi-planar forces, as they will in a game.

The athlete’s direction of movement also shapes the load the 1080 Sprint applies. “I don’t look at it as resisted and assisted when it comes to change of direction. When they are moving away from the 1080 Sprint, it applies a force against the direction of movement. When they are moving towards it, it is a load in the direction of movement. Either way, they are learning to overcome external forces to execute their movements.”

Neel demonstrates a simple, early-cycle exercise. He stands with the 1080 Sprint a few meters to his right, then performs a single-leg lateral jump off his left foot to a single-leg landing on his right foot, moving towards the 1080 Sprint.

He explains, “The jump is only one part of it. I’ll attach the cable to the back of the right shoulder. Then as the athlete lands it pulls her down and towards the machine. If it pulls her enough that her shoulder drifts out beyond her hip, she’ll lose her balance and not have the landing. Or I can attach the cable to the center of mass on the front. Now the load is pulling her forward as well as to the right, so she has to counter the forward, rotational and lateral pulls.

Without being able to decelerate into the landing and keep her center of mass over her base, she’s not going to be able accelerate back in the other direction. That’s the progression we work on.”

The single-leg static jumps progress to taking steps into and out of the jumps. This trains the athlete to overcome the 1080 Sprint in both directions in the course of changing direction. The movement patterns and control transfer to the changing and unpredictable demands of sport. Then, if a combine approaches, Neel simply needs to choreograph the specifics of the task because the foundation is in place.

“When we’re getting ready for the combine, we train every detail for how they will perform it that day. How many steps, when and how they move the hips for deceleration, how they execute the turn.”

Finding a replacement for the 40-yard dash

When Neel attends combines with his athletes, he sees an increasing number of team strength and conditioning coaches hovering over the 10-yard mark of the 40-yard dash. They are hand-timing the 10-yard split, openly acknowledging that a rough estimate of an athlete’s acceleration over 10 yards is more informative than their performance in the most-talked about event of the combine.

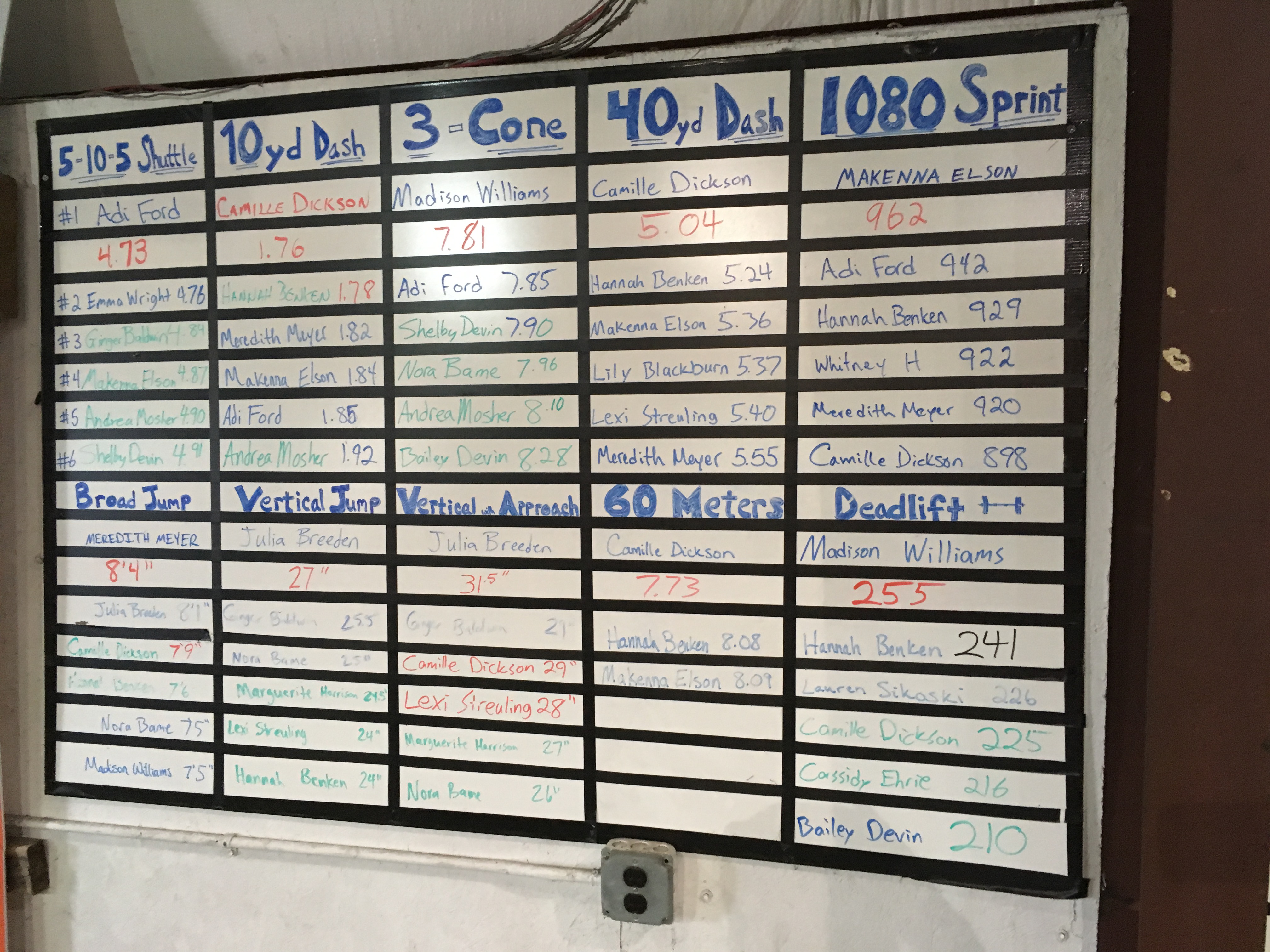

Neel and his team at Xceleration have their own standard test that they hope will gain broad acceptance: 25 yards at 10 kilograms of resistance with the 1080 Sprint. “This is the test we do with everyone. During training we adapt for age, sex, body weight and all the rest, but we believe the ultimate point of reference is 10 kg for 25 yards. It’s what we have on our leaderboards, and we want to see it become the number everyone compares down the road.”

[av_button_big label=’More resisted sprinting with 1080 Sprint’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,http://’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-19v5ozu’]

20-meter sprint kinetics for basketball training and testing

[/av_button_big]

Neel believes the universality of this test reveals abilities and potential that remain hidden by other tests, even those that are graded by age, sex and weight. He talks about a volleyball player whose performance on the standard battery of tests were far below what he expected based on her abilities on the court. She out-performed those tests and her peers on the 25-yard resisted sprint at 10 kilograms, giving Neel the long-awaited insight into her athletic capacities. Conversely, he has seen American football players with fast 40-yard dashes, high vertical jumps and all the rest fall short on his in-house standard. He then had a new, critical piece of information to shape their training.

Neel also expects this test to be an effective talent spotter. “When you see a 12- or 13-year old put up numbers that you would normally see out of a high school junior, you know the raw materials are there. That is an athlete with a large base of ability. We can be confident in recognizing what’s there because we’re making a direct comparison between athletes running the same test. Then in the years to come, we always have an objective baseline to refer to as we chart their progress, showing where they started and where they are now.”

[av_button_big label=’Next post:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/1080-sprint-clemson-baseball-rick-franzblau/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-jgtl6y’]

1080 Sprint in baseball: Resisted and overspeed sprinting to train mechanics

[/av_button_big]

The 40-yard dash is too ubiquitous and too easily digestible to be replaced any time soon. But as more coaches and athletes focus on the first 10 yards and on attributes like acceleration and force, their performances on the field will reflect the better alignment between training and testing. And perhaps over time the 40-yard dash will simply fade back and pass away.