The concept is nothing new. From Ben Franklin’s axiom an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure to Charlie Weingroff’s presentation series “Training = Rehab, Rehab = Training,” problem-solvers have long recognized the need to address the underlying causes of an issue rather than simply reacting after each issue flares up. In a clinical setting, however, this can be easier said than done—clients seek out treatment options because they are already experiencing pain or dysfunction, not from the suspicion they might experience symptoms further down the road.

Arve Hembre, naprapath at the Apexklinikken in Oslo, Norway, treats athletes and patients who not only arrive with symptoms of pain and lack of function… but these clients have often already tried every other available option before seeking out Apex.

“The meaning of the word naprapath is to find the cause of pain or disability,” Hembre says. “So, for me, as with every other therapist, we have to find the underlying cause. Sometimes it could be just overuse… the [athlete] may have played too many matches in a row and that’s why they have groin pain. But maybe we can see something in their movement pattern and the tests can show that this side is much stronger than that side, and we can offer more conclusions about why they got injured.”

[av_button_big label=’More return-to-play:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/1080-quantum-basketball-rehab-chris-stackpole/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-1aeiacr’]

Basketball rehab with 1080 Quantum: Data triumphs over timelines

[/av_button_big]

Naprapathy—a holistic methodology for treating connective tissue, with roots in chiropractic principles—attracts clients seeking rehabilitation and pain management, offering manipulations, stretching, and techniques similar to that of manual therapy. In addition to Hembre, two dozen professionals collaborate in Apex’s practice, including medical doctors, specialists, surgeons, psychologists, physical therapists, chiropractors, and an osteopath, performing services that range from nutritional planning to ultrasound examinations and sonographic guided injections to off-site surgical procedures.

“The 1080 gives us more to use in our test battery before rehabilitations, during rehabilitations, and afterwards,” Hembre says of 1080 Quantum, which the clinic has used for the past three years. “If we are planning to do a bigger treatment on, say, the shoulder, we can test the strength in different angles, just to tell the client they don’t simply need an injection, they also need to build up their capacity in the shoulder. And we always do bi-lateral testing to see if there is some asymmetry. It’s a tool we use to build better compliance, and to have a much more lively practice—it’s exciting for our clients to use equipment like that, and more fun for them than just working in a gym with no cables, no machines, only basic equipment.”

“Patient compliance is a major issue in treating various musculoskeletal conditions,” adds Stian Christophersen, a physiotherapist and shoulder expert at Apex.“Through testing of relevant movements and of specific strength measures, it seems that we can improve compliance and adherence to an active treatment strategy. Patients report that they find it motivating knowing that they are scheduled for a re-test, and so they stick better to their training. We hope that this will not only improve test scores, but also contribute in a positive way to their general health and well-being.”

To Return To Play or Not To Return To Play

Does the absence of pain imply the return of full function? Collaborating with Ola Eriksrud, Assistant Professor at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences in biomechanics and motor control, Hembre recently examined this issue in a case study on the return to play protocols for a 28-year-old professional soccer player recovering from a microrupture in his left quadriceps.

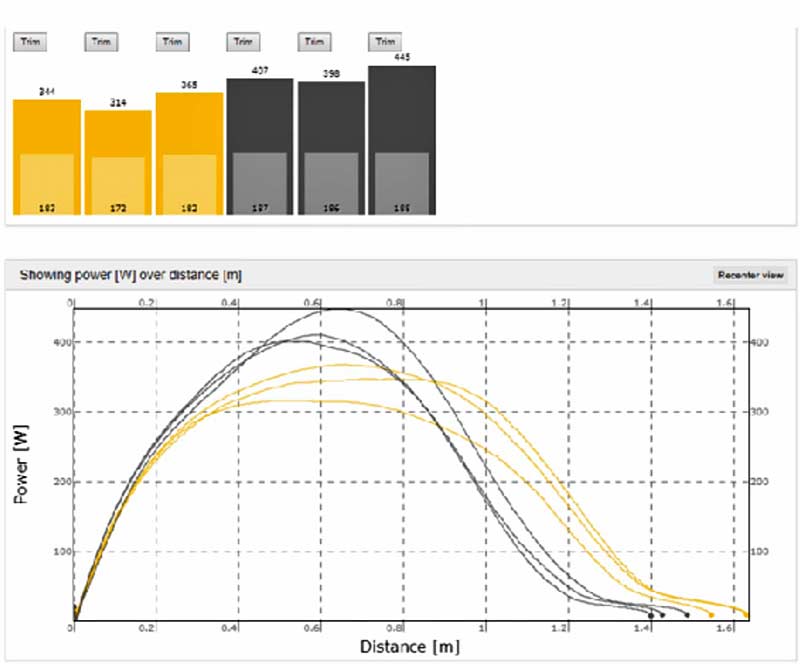

After a two-week rehabilitation process, involving both treatment and strength training methods (with light running building to more intense cycling and sprinting), the athlete felt pain-free and—in his mind—game-ready. Power-capacity tests via a simulated kick with the cable on the 1080 Quantum revealed otherwise: despite being a left-footed player, the athlete showed a significant decrease in peak force velocity in his left leg compared to his right.

“In this case study, with the Quantum we can see that the peak velocity dropped and doesn’t reach the same top [level] as the other leg, and it flattens out,” Hembre recalls. “But the patient, he felt pain-free. Nothing came up during the functional or clinical tests, but when we did the sports-specific test in the Quantum, we could see that his lack of force and power was there and therefore he maybe shouldn’t return to sports yet.”

The graphs and data offer a roadmap of progress made, and the progress that remains to be made for an athlete to return to high performance. In the case study—despite the staff being armed with the data to back up their advice that the player continue the recovery process rather than return directly to play—the athlete chose to jump back into competitive action. Powerfully striking a soccer ball places stress through the muscles of the thigh, and sure enough, 15 minutes into the player’s first game back on the pitch, he struck a ball with force and suffered a partial rupture in that same left quadriceps.

“We are hoping to see patients follow our advice and gain more compliance,” Hembre says, describing the ability to present data-backed recommendations and assessments. “With more assurance, we can say you are healthy, go back to sports and competition. That, or not only just do our clinical assessment with ultrasound and say I think you need two more weeks, it’s much easier for me and gains more compliance for them if I can point to the numbers and say you are here now, you have to be there and then you are good to go.”

Preventive Measures

“We thought that it could be a good screening test for a player to see how his body performed in soccer movements,” Hembre says. “[That method] is still under development, but it’s a start to see if there’s a lack of strength and power, or a big, big asymmetry that could lead to injury later.”

In a broader sense, Hembre and his colleagues have begun to recognize ways to address asymmetries that could lead to future injury issues. In field assessments and test batteries conducted with Eriksrud, Hembre reports that:

“We saw some players that were having their favorite side to cut into the field against the goalkeeper, and we also saw in the machine that they had much more power in that direction, and maybe that’s why they always choose that direction? So, we can give them more things to work on—if they can also get stronger in the opposite direction, they can vary more. They can do this when they train at the soccer field, but if you can give them more resistance [with the 1080 Quantum], they probably would develop faster in that direction as well and be more explosive.”

In addition to soccer players, Apex sees athletes from a wide range of sports, from competitive handball players, CrossFit athletes, and skiers to amateurs participating in tennis and golf.

“Injury prevention in sports is difficult, and it may even be unrealistic to prevent injuries 100% as athletes train to improve and compete on a high level,” says Christophersen, the Apex shoulder expert. “But, we have some data on the relevance of strength in specific movements, and can at least do our best to make sure that athletes meet these demands. For instance we know that handball players should demonstrate the same force in external and internal rotation of the throwing arm, and that loss of power in the lower quadrant significantly increases the demands on the throwing shoulder. We also want symmetry in the force couples of the scapular muscles in unilateral sports such as tennis, and through testing these various parameters we can hopefully both improve performance and reduce the risk of shoulder injuries.”

[av_button_big label=’Next post:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/defying-gravity-caryl-smith-gilbert/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-ozz38r’]

Lessons in Defying Gravity with Coach Caryl Smith Gilbert

[/av_button_big]

“We have a lot of shoulder patients, many who are older people who like to play golf,” Hembre says. “But we have simulated that maybe they don’t use their hip enough, they always use their shoulder. So we can see the strength in their shoulder, how it feels, and if you use more of the hip what happens to your force of power. We try to use this shoulder protocol with external rotation to see if it is 1:1 or 1:2. To be an athlete you have to be at least as strong in external rotation as internal rotation, and that’s a good thing to use pre-rehab and post-rehab to see how they reach the strength measurements. The question is, are they ready to do that?”