As strength and power training becomes a staple of conditioning for professional golfers, daily life precludes many recreational golfers from adding strength and power training to their game. Simply reaching the point where strength and power training becomes a valuable option requires a long-term commitment.

For golf fitness coach Ben Shear, strength and power training without the necessary mobility, stability and proper coordination of movements may send their game – and the ball – in the wrong direction.

“Our primary job is to give the golfer a chance to have a good golf swing. Then – and only then – can we add speed and power on top.

“Golf shots are triangulation. There’s the line between the ball and where you’re trying to hit it, and then there is the path your ball actually travels. How far the ball lands from the intended target is directly related to the collision of the ball and the club, known as the impact alignments. If I don’t improve my ability to decrease that angle between the intended path and the actual path, but I improve my power, the ball is actually going to go further off line. Now my good shots get better but my worse shots get worse.”

[av_button_big label=’Related post:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/1080-sprint-clemson-baseball-rick-franzblau/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-11hwcwm’]

1080 Sprint in baseball: Resisted and assisted sprinting to train mechanics

[/av_button_big]

This is why most golf training is about creating better body movements, which move you more towards perfect swing mechanics. Without putting the club head dead center on the ball, a stronger swing creates a conflict between two common goals among golfers: hitting the ball further and lowering their score. Misaligned movements from misguided strength training can also work against the goal of simply wanting to play golf pain-free.

The challenge in all this is how much the demands of the sport clash with golfers’ daily lives outside of the sport.

“No other sport in the world demands so much end-range of motion as golf. Yet the typical amateur golfer is someone who sits behind a desk at least 40 hours a week. These golfers most often have limited thoracic spine and hip mobility. These common physical restrictions, amongst others, directly and significantly affect swing mechanics. People hit the ends of their range of motion long before they ever learn how to get an efficient, powerful and repeatable swing.”

“People who are committed – juniors, men, women, any level – they get to progress to strength and power.”

Ben Shear has taken golfers through this progression since he started working with his first PGA Tour player in 1998. While Tiger Woods was redefining the sport, few golfers and fewer coaches brought strength & conditioning into their training. “When I first did it I was doing functional-type exercises and range-of-motion work, with a core base of big lifts. I was still doing dead-lifts, heavy pushes and pulls and the like.”

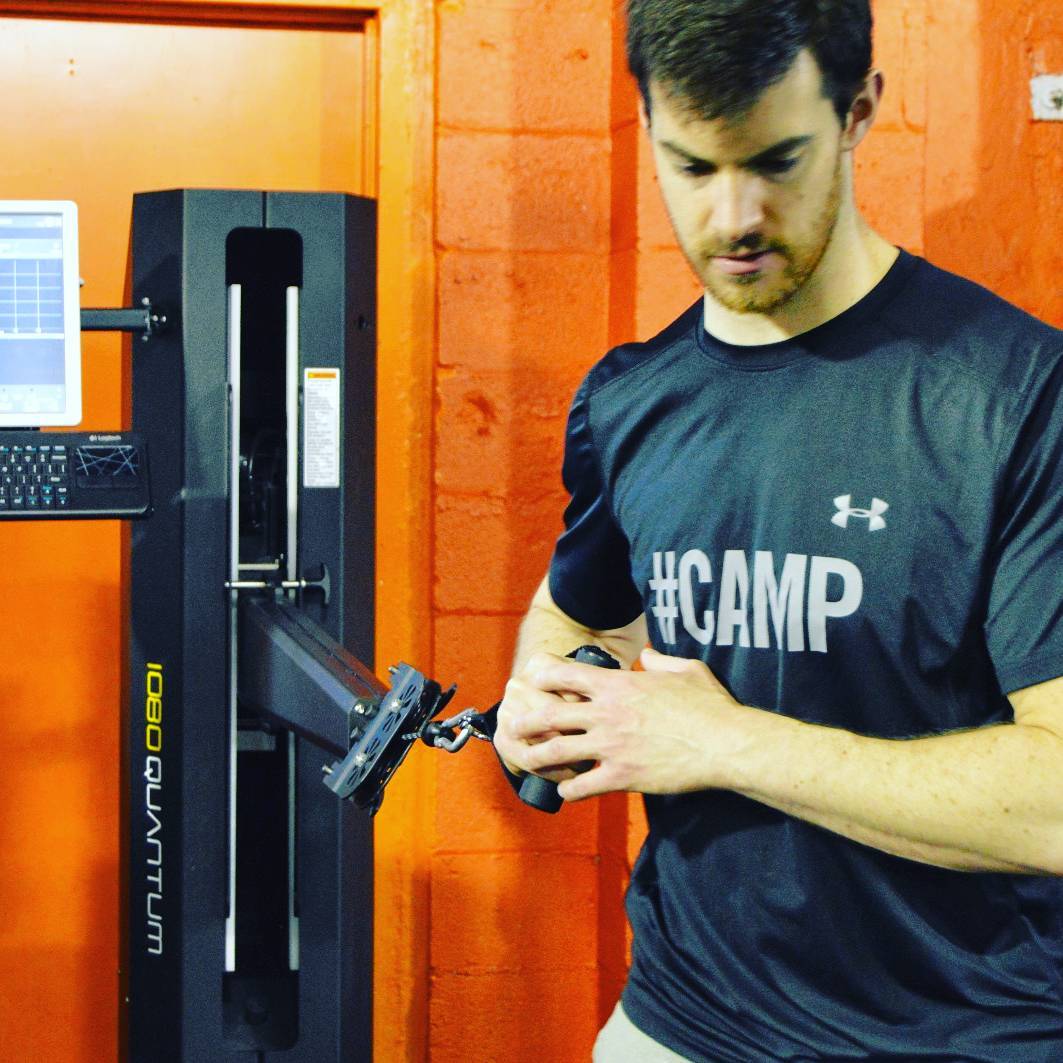

“But now you have the science and tech where we’re looking at 3-D reports, finding nuance in biomechanical reports based on swing. We look at timing from movements on the 1080 Quantum or 3-D video to see acceleration patterns while you’re swinging the club. The amount of information we have now allows us – at times – to pinpoint specific details to measure golf swing. We then turn around and can say ‘Oh, I need more RFD there, more deceleration there, etc.’”

The data allows Shear to extract the movement or timing patterns a golfer needs to improve, and find the most appropriate drill or exercise for that goal. “It doesn’t have to be in golf posture or be golf sexy. An individual drill doesn’t have to look like golf, if you can couple it together with others that do transfer into the swing.”

Shear gives a low-tech example of an exercise that ties into his high-tech training and monitoring.

“Take a medicine ball rotary chest pass. If I’m standing with my chest facing the wall and I’m doing a rotary chest pass to fire it off the wall, it’s push-pull and torque with the feet. With this, I am training more rotational forces, which MAY be exactly what a certain golfer may need. If I face perpendicular to the wall, it’s more similar to how a golfer would address the ball. I still have push and pull, but I now have a bigger weight-shifting component. I’m loading into the back-side (trail leg) and transferring my weight in a lateral shift with rotation onto my lead-leg, as you would while golfing. While this may seem like the better option, the truth is that some golfers may already have too much lateral motion, and the first version may be more optimal for them. It is always player-dependent.

“If I do these similar motions with a 1080 Quantum I get a charted trace of the entire movement, rather than just a peak number from a ballistic ball, or no data at all from a traditional med ball. Put the visual feedback on the TV screen, and now the golfer can see, for example, if they are hanging on the back foot, which slows their acceleration and they end up with less than optimal output. This is just one of many possible examples. We then can train the proper movement, they start getting forward and now they see what it looks like to hammer it.

“The 1080 Quantum is awesome because I can quantify weaknesses and speed, showing someone how when you get the weight moving forward sooner the power goes up.”

[av_button_big label=’Next post’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/bob-thurnhoffer-loyola-university-1080-sprint/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-ttxy0m’]

Loyola University track and field: Excuses are not in the budget

[/av_button_big]

Ben Shear’s work takes his clients along the path from restorative to corrective to performance. Once he has people moving the way they are meant to move, they are in much better condition for their golf pro’s to fine-tune their swing. Only then can they see the return of a lower score that comes from higher power. “At the end of the day, if you are a well-functioning human being, you have the potential to be a good golfer.”