The stadium is packed with 50,000 boisterous fans. The athletes—locked in a battle of grit, guile, and absolute strength—have competed and trained for three years just to qualify. It is a sport of sudden triumphs and centuries-old traditions; it is a sport of ruthless gamesmanship and respectful customs. It is a spectacle. And, for those living outside the borders of Switzerland, there’s a good chance you’ve never so much as heard of either the sport—Schwingen—or it’s veritable Olympics, the Eidgenössisches, a Schwingfest which draws the best of the best to compete every three years.

For the newly initiated, there’s an elemental simplicity to Schwingen that anyone familiar with grappling sports will understand: burly men dig in to uproot and throw their opponent, with the match ending when one combatant’s shoulders are pinned to the ground. Schwingen also features the esoteric, cultural quirks that add a unique appeal to other traditional sports like Sumo wrestling or the Highland games: the schwingers wear lederhosen-like trousers and collared shirts inlaid with jovial, Edelweiss patterns. Squaring off in a pit of sawdust, as an act of sportsmanship, the winner traditionally brushes the woodchips from the loser’s back.

[av_button_big label=’More with Arno Galmarini:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually, https://1080motion.com//1080-quantum-hmmr-podcast-arno-galmarini/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-154cfr9′]Five highlights from HMMR Podcast with Arno Galmarini[/av_button_big]

“I always wanted to work with an athlete from Schwingen,” says Arno Galmarini, a Swiss strength coach and former gym owner who has spent the past decade training hockey players, Alpine athletes, soccer players, cyclists, and more. “Where my gym was based in Zurich, it’s one of the biggest cities in Switzerland—and usually traditional sports aren’t as common in the larger cities, so Schwingen was scarce. Then, I was introduced to Noe Van Messel.”

Country Strong Meets LTAD

Galmarini began working with Van Messel when the schwinger was just 16 years old—in a sport with no weight classes, the young athlete already had the natural size to hold his own, measuring in at a formidable 190 cms and more than 100 kilos (over 6’2” and 220 lbs).

“With Noe, in the beginning, he was big but he wasn’t strong. I remember, the first time we did a trap bar deadlift—and the deadlift is one of the movements we train a lot—he lifted about 60 kilos and after 10 reps he was completely tired,” Galmarini says. “Usually I start with time under tension, so slow movements just to make sure the technique is right, but he was done. And when we did some single leg squats as well, with 5-10 kilos in each hand, he was tired already after a couple of reps. He had good raw strength, but not good endurance or anything like that so we really had to start almost from scratch building a good fitness level.”

In addition to the wide gap between Van Messel’s enormous potential and minimal training age, Galmarini also had to work around the teen’s busy schedule: the young grappler was still a full-time student. In that process of starting from scratch, Galmarini initially set out to teach fundamental movement and lifting patterns. Ultimately, his long-term plan with Van Messel was to incorporate the 1080 Quantum in his training, taking advantage of the system’s capacity to train sports-specific movements with varying modes of resistance. Before moving on to those advanced methods, however, Galmarini and Van Messel first needed to master the basics.

“In the beginning we didn’t work much with the Quantum, as I first wanted to get him introduced to the movements and get him stronger in general,” Galmarini says. “When we started to introduce the Quantum we just did basic single-leg squats so he got a feeling for how the Quantum feels, which is something I do with all my athletes, they really need to get used to the Smith Machine, they need to get used to the modalities, like how it feels with eccentric weight. There is always an adaptation phase in the beginning, before we try to involve some more special movements where we really use the strength of the Quantum.”

Sport Is Sport—Performing a Standard Needs Analysis

Even in a sport that traces its roots to the 17th Century, a high performance coach still needs to take a fresh set of eyes to the event, asking the right questions and evaluating the key performance indicators for success.

“Breaking down the movements and really looking at each individual part was very important to me,” Galmarini says. “Looking at when they pull, which joint angles do they use? When they are on the ground, how do they move? What kind of energy systems are in place? How fast or how slow are the muscles contracting in certain positions and movements? They need a lot of flexibility to be able to twist, because when your shoulder blades are on the ground, you’ve lost.”

As with most combat sports, Galmarini recognized that Schwingen balances quick and explosive movements with extreme bioenergetic demands, requiring both speed/power development and sufficient aerobic capacity to manage the rigors of a full-length match and be able to recover as fast as possible between pulls/throws.

In the pit, each contest begins with the competitors locked in a grip on the waistband of their opponent’s trousers, initiating a slow-motion ballet as they prod for a first attacking maneuver—beyond the grip strength on display, these opening gambits are akin to an extreme isometric, with each athlete fully braced against the other. In order to truly appreciate the physical demands of these clutch positions, Galmarini—bravely—stepped in to spar with Van Messel.

“You don’t really see it as a viewer of the sport—when they are basically grabbing each other and walking around, you think oh, they’re just doing nothing, just walking around. But actually they are trying to position themselves, and they are already pushing and squeezing very hard,” Galmarini says. “Once, when I was sparring with Noe, I tried to get into my position but I couldn’t because he squeezed me so hard and he pushed his shoulder into my chest so I couldn’t breathe. He did that on purpose, just to take out my breath. So all these details, you don’t see it from the outside. But it’s crucial to get the opponent tired and not let him get into certain positions to make their pull.”

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

Two years ago, preparing Van Messel began with a clear goal—to take the 16-year-old athlete (then competing at the “juniors” level), up to where he could qualify for the 2019 Eidgenössisches Schwingfest in Zug. Beyond Van Messel’s youth, inexperience, and ongoing academic demands, there was one more complicating factor—the schwinger was just coming off of an ACL rupture.

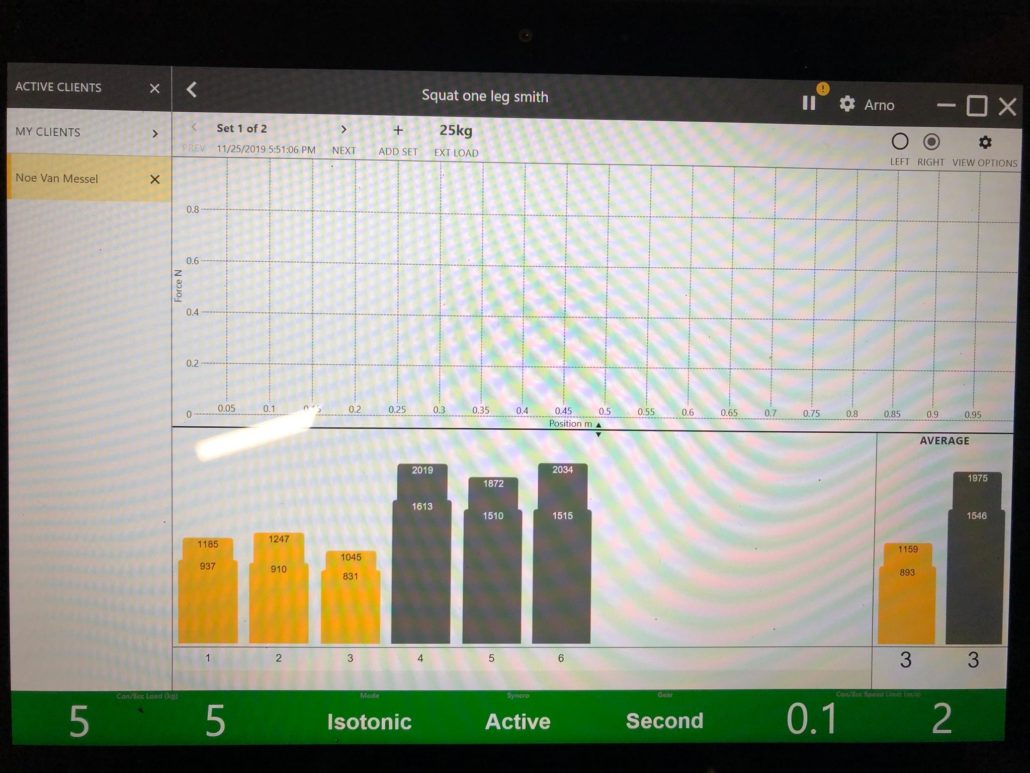

“During the rehab phase, we did a lot of testing with the Quantum just to see how we were progressing,” Galmarini says. “So we did mostly single-leg squats to test left and right imbalance. We didn’t start with jumps or faster movements until that imbalance was below 10%. You shouldn’t start any explosive movements until you are below 10% right/left leg difference. Once you are under this threshold you can start building up all the jumping exercises again.”

Once Van Messel was further along in the return-to-perform continuum, Galmarini began incorporating work in the Quantum’s Isokinetic mode to build up the athlete’s overall strength. The process was instilled with a sense of urgency leveled with pragmatism. They had a fixed timetable—Van Messel was highly motivated to qualify for the Eidgenössisches—but moderate expectations. Like a young athlete getting their first taste of the Olympics or a World Cup, the primary objective was to gain critical experience to advance through the ranks in the next one.

Following an efficient rehab, after successfully qualifying and competing in the 2019 Eidgenössisches, Van Messel continued to build on that momentum, taking on an aggressive schedule of smaller Schwingfests to catch up for the time lost due to that ACL injury.

And then… he the tore the meniscus in the same knee.

“When he got injured five months ago, he had six weeks in which we couldn’t do much,” Galmarini says. “We’d already done a test on the Quantum, so that was our baseline to see where we are and especially what is the left/right difference. Then, what was really crucial was that we trained the healthy leg as hard as we could, because research shows that if you train the healthy leg, it helps to keep the strength and muscular cross-sectional diameter higher in the injured leg.

“Three weeks ago he was under 10%, and now he is actually the same in each leg. So right now we are using the Quantum again and we are mostly doing single-leg squats, but soon we’ll introduce the deadlifts again with the Quantum.”

From General to Specific

On the heels of a pair of significant injuries, the needs analysis for the strength coach becomes quite simple: stay healthy! To that end, Galmarini has geared his recent training for Van Messel toward building general, robust strength. Galmarini also works closely with Van Messel’s technical coaches on load management and recovery monitoring.

[av_button_big label=’Next post:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually, https://1080motion.com//key-exercises-post-acl-return-to-play/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-pu1hkj’]5 Key Exercises to Determine Return-to-Play Readiness After an ACL Tear, By Kyle Davey[/av_button_big]

“We’re really working closely as a team,” Galmarini says. “What I try to do is give (the technical coaches) exercises to do in the Schwingen training. So, for example, when it gets more specific, we would do intervals where I would say give Noe two or three important drills that he has to repeat to learn, and I’ll give you the time for how long he should do those drills and how long the rest breaks should be in-between. I give the rough boundaries for the exercise, and the coach is looking at the technique to see if he’s doing it right.”

Though their current training phase is more general, Galmarini looks at the specific demands of each day and organizes the intensities accordingly.

“For example, on Monday we can plan a high central nervous system day where we use the Quantum, and then on Tuesday Noe goes to Schwingen, and there we don’t want to do power and intensity throws, we want to do more bioenergetics, which is lower intensity. And then we would do some drills like I just described—maybe isometrics for 30 seconds to a minute, and then a break, and doing that in an interval fashion.”

Though they’d moved beyond some of the basics with the Quantum to incorporate more rotational work and lifts targeting Schwingen-based movements, looking ahead Galmarini hopes to involve the Quantum in even more specific training exercises, such as pinpointing the lead grip on an opponent’s trousers.

“From full range deadlifts I was going to partial deadlifts, because when you look at the pulling movement, it’s mostly the last knee, joint, and hip angles where the Schwinger really pushes the most. We tried to make that specific, but I always had in mind that the next step we’re going to do is something with the trousers—using that in isometrics or rotational pulling movements.

“We haven’t done it yet because injuries set us back,” Galmarini says. “But since I’m able to work with him over a long span of time, I can really think in terms of what I’ll do in one year, two years, and what’s my long-term plan.”