Visit the website for any management consultancy and you’ll quickly find their white paper on how to transform your organization into an “analytics-driven organization.”

That phrase came to mind when I saw a Twitter thread by Dr. Stephen Shea. The audience for those white papers – the prospective “analytics-driven organizations” – are already warm to the idea. They have some of what they need, the data, the processes, the white boards, the quants. Now they just need the outside help to bring it together (for a healthy retainer).

But Dr. Shea knows an entire industry that needs to take a few steps just to reach the white-paper stage. He is the chair and an associate professor of mathematics at Saint Anselm College, and the author of two books (one hockey, one basketball) on sports analytics.

“One of the big challenges is the long history and strong culture in sports that are not analytics-driven. If we are tasked with bringing analytics into an organization,” he said in response to my hypothetical assignment, “we have to be understanding of that reality.”

Dr. Shea identifies one person missing in most sports organizations: Superman. An analytically-trained, business-savvy, sports-minded Superman.

“The most important piece of any analytics staff in a sports organization is the ‘Superman,’ of sorts. This is somebody who can sell analytics across the organization and who can understand the other elements of the operation well enough to speak to them, while still listening and learning from them. This individual is an analytics hire who can cross over and stand courtside during practice – someone who wants to – to see what the teams are doing. They fit in with the coach and the players, speak their language, share their conversations.”

1. Warning: this will be a philosophical thread on sports analytics. I've never viewed sports analytics' purpose as to provide answers in the most complete sense. Sure, a stat model can provide an answer to a stat question, but no model can account for all the variables.

— Steve Shea (@SteveShea33) April 6, 2018

As if that description does not filter the population enough, Dr. Shea then expects that person to brief and convince the general manager or vice president of sport operations. And then from the boardroom they go back to the training room, winning converts and arguments at every stop.

Not surprisingly, Dr. Shea does not encounter Superman very often. He is used to seeing a general manager or assistant general manager preside over the analytics operation as the “idea person, the center-point where all the information comes together. They have their analytics staff, but they keep them at arm’s length.”

“There’s a breakdown there because these very intelligent and savvy general managers often don’t know enough about the analytics operations to function in that Superman role. And they often have so many things on their plate they can’t give it the appropriate focus. They have a full-time job, and then they try to take on this other full-time job, which should involve being the vehicle of communication to the position they are in.”

The ideal analytics driver has an equally high level of sports knowledge, business acumen and statistics background. The analytics shop in the organization has plenty of room and need for both specialists and generalists. “Stats are stats and database management is database management,” Shea says. “And within the group you can have people who are highly specialized,” whether in statistics, software programming or sports science. But they must be under the direction of the polymath, the person who can shuttle between the coach and the analytics shop with nothing lost or weakened in translation.

Basketball is Dr. Shea’s first love and was the subject of his first book, but he put his first serious analytics efforts into hockey. About 12 years ago he saw the opportunities hockey presented because so little analytics work had been done in the sport. “At some point” he switched over to basketball. Basketball was further along the analytics curve and therefore more receptive to his work and ideas.

As he comes back into hockey, teams are determined to learn from other sports’ experience. Hockey front offices and coaches ask Dr. Shea what is happening around the industry. He sees commonalities in what the different sports do with their data, and also with what they neglect.

“One area where many sports under-utilize analytics is in the X’s and O’s on the court. We see some changes in basketball, baseball and soccer where teams look for market inefficiencies. There are some significant changes in basketball in player usage, how games are played and schedule changes.

“Hockey, despite being a much more demanding sport physically, we’re not seeing those changes. Hockey teams are looking at things like player health, injury prevention and roster construction. It’s the same shifts and same rotations as it has been for however long. Unless hockey just got it right at the beginning, they are not doing something.”

[av_button_big label=’Bookmark for later’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/sports-data-ryan-smyth/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-1n60mxz’]

Sports data making up lost ground on the technology that produces it

[/av_button_big]

Using analytics to create a context for actions on the court or rink – turning the X’s and O’s into x and y, and back again – is at the heart of Dr. Shea’s work. For hockey, this involves rethinking and revaluing game assessments.

For his book “Hockey Analytics: A Game-Changing Perspective,” Dr. Shea studied situations where one team had a positional advantage. The majority of goals came from these situations: transitions, odd-man rushes or momentary overloads in the attacking zone.

Focusing on this relatively small subset of possessions revealed the amount of “blah” (his word) as the game goes back and forth with the teams at positional parity. Recognizing that it is not the location of the shot but the context of the shot changes how analytics can predict the chances of success, and how coaches should train their players to move. The data drives the tactics, and the outcomes drive what he collects.

“A possession should be the fundamental unit of analysis. If you get a two-on-one break there should be a certain chance of scoring. Whether the players bumble it, take a shot or get two shots on the rebound, it’s the danger of the possession – not the danger of any individual shot.”

The location of the final pass before a shot can greatly change the probability of success. If the pass comes from the same side of the rink, the goalie is already covering the angle when the shot comes in. If the pass comes from across the ice, the goalie has to slide from post to post. Where was the goalie when the pass started? How much time did he have to react? Where was he when the shot was taken? Did he have time to square up to the shooter? Did the shooter corral the puck, or did he shoot one-time?

Two shots from the same location in very different circumstances produce very different statistical – and real-life – outcomes.

Understanding the build-up, context and positional advantages gives Dr. Shea the chance to rattle the conventional wisdom. “We looked at the numbers and found that how some teams pinch in the zone is questionable. What’s the advantage gained from winning the puck if you challenge in a given position? Why go into a board battle and leave the space open in front of the net?” These questions cut to things hockey players learn early in their youth days, and carry with them through the professional levels.

These analyses rely on positional data increasingly available via wearables and in-arena video systems. Dr. Shea partners with ShotTracker, a wearable for basketball analytics. Such technologies provide accurate, convenient and voluminous data, but nothing fundamentally new. They enhance the human eye, but do not provide anything a trained observer could not already see. It would be expensive and time-consuming to have a team of video analysts record “Cross-ice pass / zone 2 to zone 4 / left wing to defender / one-time shot / weak side / pad save” for every play in every game for a given team or league. But it could be done.

Not all data is publicly observable, though. Biomedical sensors are making their way into wearables and clothing. And while cameras can gather the spatial and performance data, the biomedical data requires the players’ active participation: they have to put the sensor on their body. Their cooperation is as much a condition of the data collection as the availability of the technology.

Dr. Shea takes a firm stance on the two types of data on the grounds of both privacy and compliance. If a technology measures something you could measure manually and from a detached perspective – however tedious the process may be – Dr. Shea has no problem with that data being in the public domain.

But the compliance issue stands athwart the debate about the availability of biomedical data. Players immediately surrender a certain level of privacy and control once they put a device on their body that can see what no one else can see. Think about signing up for Facebook. We click through the terms and conditions, forfeiting some level of privacy while retaining the right to complain about it later. But we at least did so fully voluntarily, and complain we will. Dr. Shea doubts players have either comfort.

“A lot of teams have made these optional, but in reality, it’s not always optional even if it is optional. I don’t think a pro team should even require heart rate or fluid intake. All of these things can be helpful to a player, and if you’re working with training staff there is some medical stuff they do need to know. But the pressures of sport, fighting for a spot on the roster, coaches and staff ‘suggesting’ something – there are some fine lines there.”

Many on the sports side do not credit the distinction. Older players, for example, do not want managers to confront them with quantitative data showing how much they have slowed down over the past two seasons when they come in for contract renewals. But everyone already knew they were slowing down. Everyone could see it, so does the number make much of a difference?

As far as the “public” data goes, though, Dr. Shea hopes for the day when athletes can opt to make their data centrally accessible to coaches, scouts and analysts. Housing athletes’ performance stats, spatial tracking data and game film together would create efficiencies throughout the development pipeline.

This could particularly help teams and athletes in remote areas. Collegiate and professional scouts only have so much time and money to travel in search of prospects. They will go to areas with a large density of young athletes: cities, “feeder” clubs or known hubs of talent. This overlooks athletes who may be just as good, but are off the normal travel routes. “I’ve talked to U17 provincial teams in Canada where they are not seeing college scouts come through as much. They have the talent, but not the density of talent, to attract the scouts.”

The analytics-driven organization white papers talk a lot about building the right corporate culture. Ever the educator, Dr. Shea zooms out to the broader culture.

[av_button_big label=’Dr. Stephen Shea on Amazon’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://www.amazon.com/s/ref=dp_byline_sr_ebooks_1?ie=UTF8&text=Stephen+Shea&search-alias=digital-text&field-author=Stephen+Shea&sort=relevancerank’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-1daca5j’]

Basketball Analytics: Spatial Tracking and Hockey Analytics: A Game-Changing Perspective available for Kindle

[/av_button_big]

“As a math professor I often think about the influences of our culture in the US in terms of how we respect and use mathematics. It is certainly the case in the US that for a long time we haven’t relied on the scientific information behind coaching and sports science. Coaching hasn’t been evidence-based. But nursing and education have not been evidence-based for that long.”

So what advice would Dr. Shea give to a student who asks: Professor, I want to be Superman for my favorite team. What do I need to do?

He points them to improve on four fronts. “Take as many mathematics and statistics courses as they could fit into their schedule. The top priority is an upper-level statistics offering, but other courses are helpful as well.

“I’d recommend at least a year of programming: C++, Python or really any language. I find that the good students, once they learn one programming language, can teach themselves others. If they can fit it into their schedule, they should also take a course using SQL.

“If they are not playing a sport, they should be around and involved in sports. Volunteer to keep stats for a college team, look around to the local pro teams, including minor league or junior affiliates. Some internships can even be done remotely.

“Finally, practice constructing and communicating quantitative arguments. Part of the Superman’s role is being a salesman. The Superman has to take all of the data from the analytics group and construct a narrative that will persuade a general manager or coach. Start a blog, converse on social media, enter papers at conferences. Anything to develop the habit of using quantitative arguments when debating sports – even with your friends.”

[av_button_big label=’Next post:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/ato-boldon-1080-sprint/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-n0l7pj’]

Ato Boldon’s turn to coaching moves him outside the lanes of track and field

[/av_button_big]

Four steps on the path to Superman. In time, Saint Anselm College may come to be the Krypton of analytics-driven sports organizations.

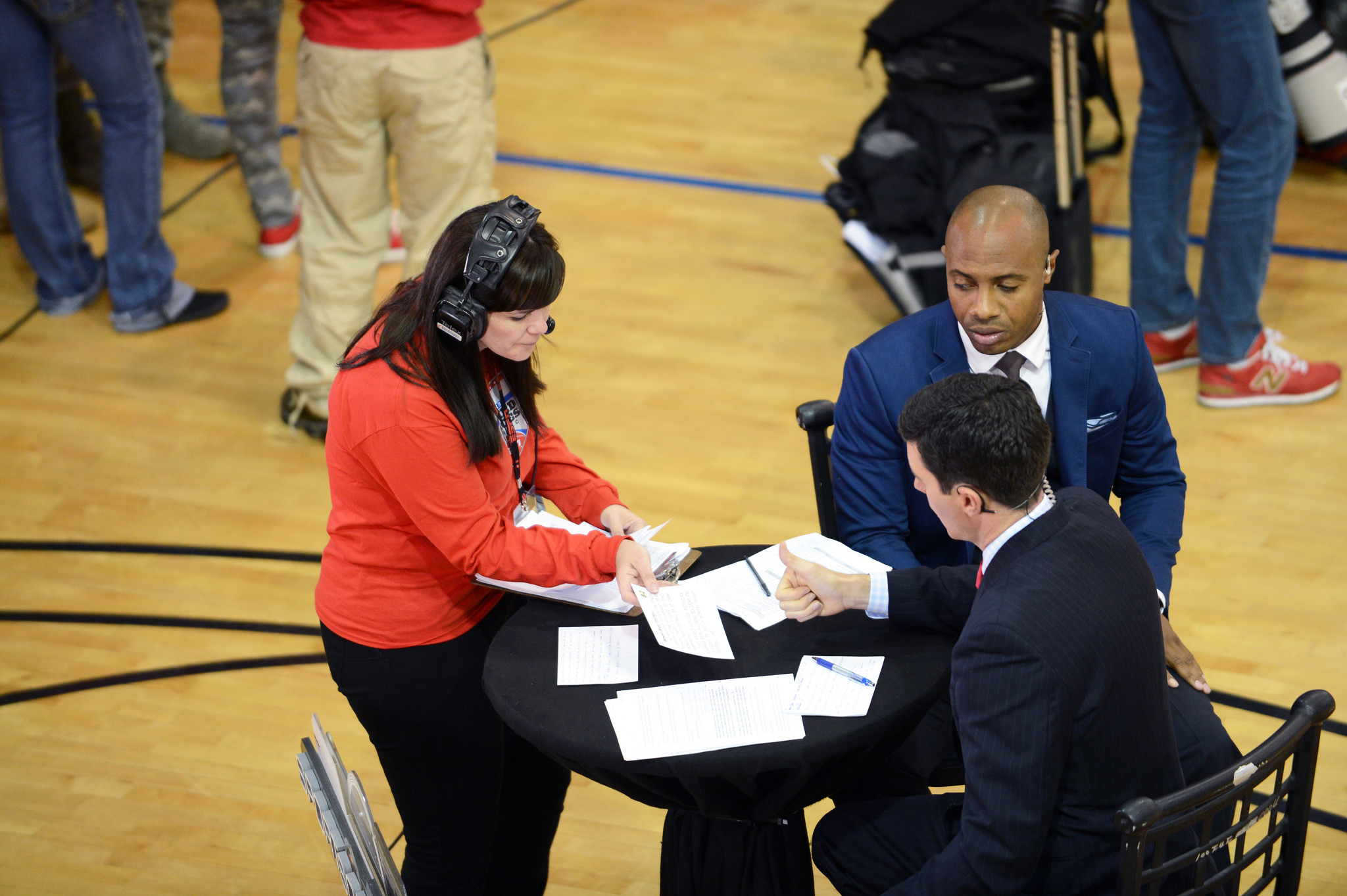

Cover photo: US Army photos, CPL Jae Sang Ma (Flickr / CC By 2.0)