An emerging consequence of the growth of sports technology over the last 10 years is the messy proliferation of sports data. Every device and every app captures and creates data by the megabyte to describe each stride, rep and heart beat for every athlete using the system.

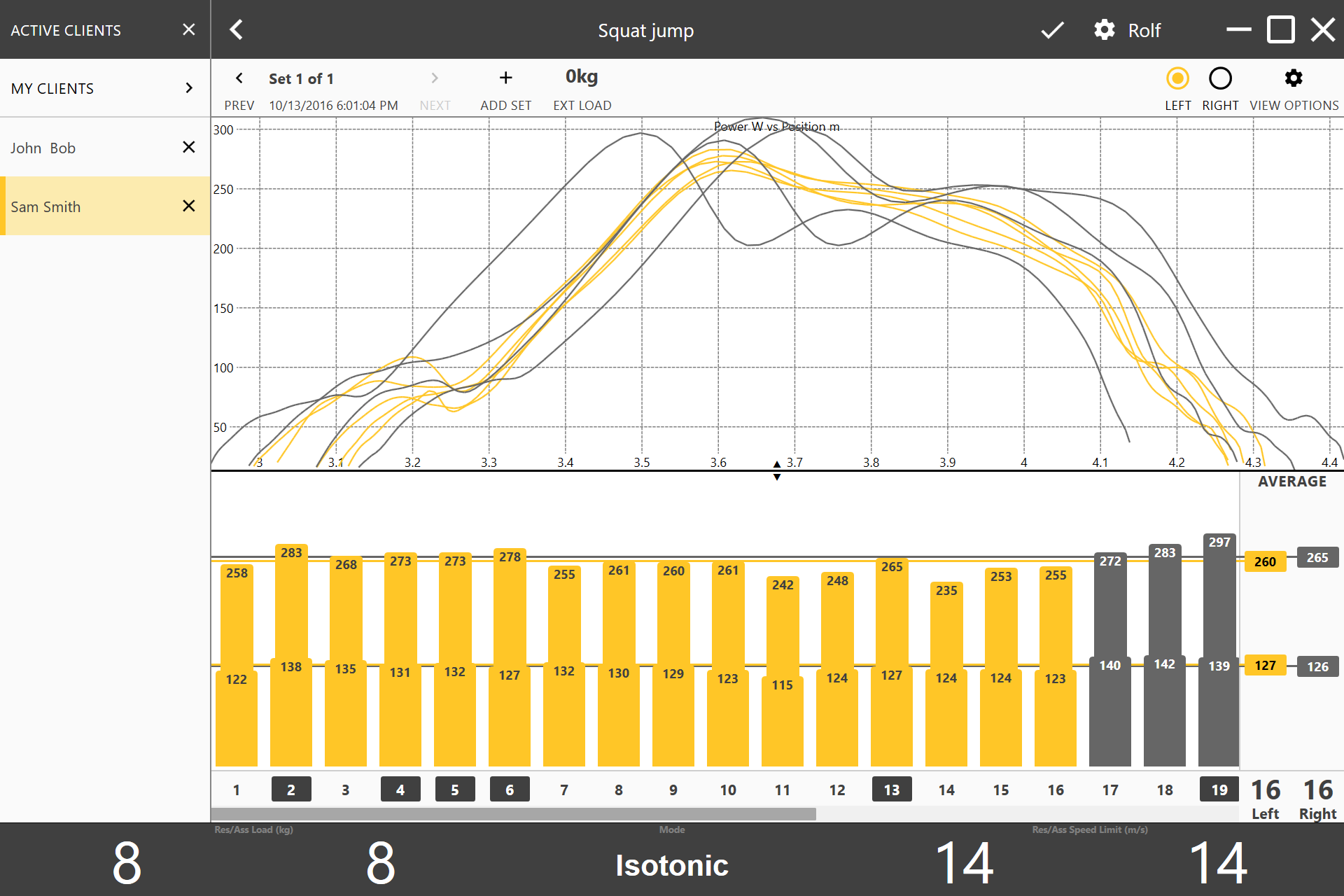

The most successful products – the ones that are coming through the industry’s current period of consolidation – are the ones that presented reliable data in an understandable and actionable format. The innovation and the technology were only enough to come to market. No matter how many times a coach would say “I’ve always wanted to do / know this but it’s never been possible before,” if he could not use the data to assess the current workout and plan the next one, the technology fell flat.

After several years of using a product, though, the usefulness of the accumulated data starts to plateau. Player dashboards built to show daily, weekly and seasonal snapshots do not help a coach use that technology to full advantage of the course of her time with an athlete or team.

Moreover, athletes come and go from a team all the time. High school athletes switch sports, college athletes transfer schools, professional athletes are traded or transferred. If the previous institution did not use the same technology or the same athlete management system as the new one, the new coach is starting at square one with an athlete many years into her development.

Recognizing limitations of built-in sports data analysis

Ryan Smyth is a technologist and sports data consultant based outside of Toronto, Ontario. He advises teams and coaches on how to make sense – and then productive use of – the accumulation of data from their sports technology. Smyth cautions that there is a limit to what strength and conditioning coaches can do on their own with these massive data sets. At some point, their team or school may need to hire a dedicated analytics staff. But up to that point, coaches can still see many of the benefits of the tech and data.

“Strength and conditioning coaches are often left with the task of implementing the technologies, collecting and sorting through the data, and also creating reports designed to explain (and justify) the work they’re doing to the players and the rest of the organization. It’s a lot to take on, it’s a full time job.

Over 92k biometrics collected. Great day of testing. #camp #ohl #oshawagenerals #GoGenerals pic.twitter.com/HUATzCfQk3

— The Park (@the_park_sports) August 30, 2017

“My advice is to choose two or three pieces of equipment and hone in on what’s important and ignore the rest. The best way to do this is by filtering the information into an athlete management system, but even an Excel spreadsheet with some simple built-in formulas can help weed out the noise and streamline the data. Trying to do more without the support of an analytics and/or monitoring team will ultimately fall short of what you’re trying to achieve.”

Smyth laments the tendency for the different stakeholders in an athlete’s performance team to silo the data they obtain. The lack of sharing is a “missed opportunity” to understand all the factors that contribute to an athlete’s current state of performance.

Sports data ownership can improve long-term performance

That holistic view would not only be a stronger basis for future training and development, but would contribute to the overall body knowledge about how athletes develop and respond to training.

“This is a pretty heated topic that’s just starting to surface lately. When all this new technology started hitting the market several years back, no one was paying much attention to how things would be handled down the line. The idea of ‘data ownership’ wasn’t even part of the conversation, really.

[av_button_big label=’More hockey from 1080 Motion:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/hockey-summit-1080-sprint/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-112as6g’]

Fusing testing and training with the 1080 Sprint at the Hockey Summit

[/av_button_big]

“So now we have this situation where athletes have this fragmented data history that starts and stops with whomever conducted the test(s). Teams have data on their players that begins and ends with that particular organization, team doctors have one set of data, while personal rehab doctors might have a completely different set of data, and no one’s sharing anything.

“But this is a missed opportunity. Imagine the benefits of seeing a player’s entire history of biometric, physiological, and statistical data all together. There would be greater buy-in, and you would see improved performance, fewer injuries and hopefully longer careers.

“If we can get things to a place where an athlete’s personal data logs are treated the same as one’s medical records – where the player controls how the data is shared – that’s when the data really starts to gain some value. There are some big ideas that are starting to gain some traction lately that seem to be pointing in this direction.

[av_button_big label=’Three highlights from GAINcast interview with Ola Eriksrud’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually,https://1080motion.com/ola-eriksrud-gaincast-highlights/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-lufpbc’][/av_button_big]

“I’d predict that, within the next few years, league-wide sports data management systems will become the standard. And that’ll be the basis for this kind of system to really take flight.”