Georg Pfarrwaller has done his research. Studied JB Morin’s work on improving acceleration, tested out flywheel training and VBT apps, and tinkered with different loading parameters and periodization models. Coaching for PluSport, a Swiss organization dedicated to developing Paralympic athletes while also offering recreational athletic opportunities for individuals with disabilities, Pfarrwaller faces the dual challenge of teaching a proper technical model while also adjusting that model for each athlete’s unique limiting factors.

(Lead image courtesy of parathletics-nottwil99 with Ennio Lenza / Keystone SDA)

“The blades are made to work well in upright running,” Pfarrwaller says, describing his training with a competitive sprinter who is a double transtibial amputee. “It’s very easy when they are fast, they’re very efficient and we see that in the 1080 Sprint when we do overspeed runs. You have this value with the force average, and it’s approximately zero. She flies over the ground. But with the missing ankles, for acceleration she has to learn to coordinate the knee and the hip to bring her artificial foot in the right position and with the step project herself forward instead of upward.”

Asking Questions, Finding Answers

“Sprint training must above all be of good quality. I want to get the athletes to give one-hundred percent also in training, at least in a few runs,” Pfarrwaller says. “My question over the past two years was nevertheless always how do I find out what is the right training method to get an individual better? I looked for methods or measures or tests which might answer my question, does an athlete need more speed training or do they need more rest or do they need more weightlifting? And then, is it hypertrophy or is it coordination or is it power or is it force training?”

[av_button_big label=’More speed training:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually, https://1080motion.com/next-generation-german-sprint-training-david-corell/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-154cfr9′]The Next Generation of German Sprint Training[/av_button_big]

Each of these questions requires an individual solution for Pfarrwaller’s athletes, as beyond their different abilities, they also have different indoor or outdoor seasons to prepare for and different training schedules, with training frequencies that range from four sessions a week to twice a day. Regardless, it is an important task to bring the different athletes together in training sessions. They can not only push each other, but also learn from each other.

“The 1080 Sprint really helps me to answer my questions for what each athlete individually needs,” Pfarrwaller says. “It’s very hard for me to have this uncertainty in training—they just have one sports career and I want to be sure I give them a good program which fits them.”

Adding Resistance and Assistance

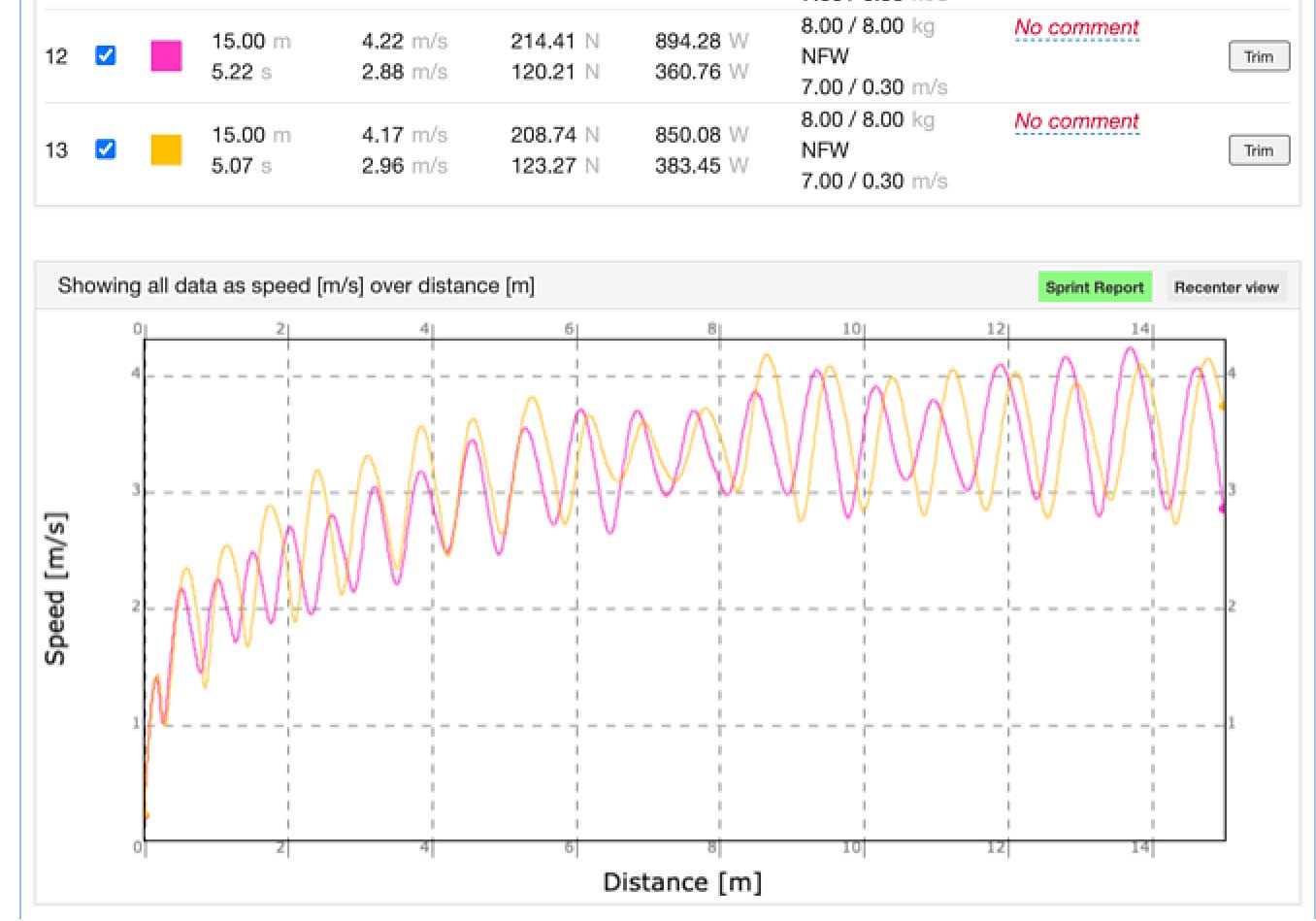

With his double-blade athlete, programming resisted sprints with the 1080 Sprint and tracking the outputs on her power graph provided Pfarrwaller with crucial insight into where to focus his acceleration training.

“We saw that she’s really good pushing in the first steps, but then we have less than 100% pushing on step 3-4-5-6-7…and then she becomes better after 7 or 8 steps and her power values go up again,” Pfarrwaller says.

“At first we started with different loads and now I am training on this velocity at 50% the way JB Morin describes in his work. And we do one week where we train with this 50% velocity, the load is very high. I have some athletes that have 24 kilos of resistance, and the blade runners have 10-11 kilos of resistance. Then after one month we retested and saw that it was good, the theoretical load is right. Then, in a second phase, we trained with a different load, with heavy loads, a 75% velocity load. And after a month I saw that the force was getting better again like in the first period. In the next phase, I’ll try to find out what kind of training brings them more velocity.”

On the max speed side, in the years before he was utilizing 1080 Sprint, overspeed work was something Pfarrwaller would introduce 5-6 months into the season. This stimulus was something he programmed only after a long preparation phase, and even then many of his athletes performed overspeed sessions grudgingly.

And now?

“(This year) I started with assisted sprints on Day Two,” Pfarrwaller says. “I told my athletes to just run easy and try to find a very efficient way to run. We began with the assistance under their top in-season speed. The first step was to learn to run very easy, in the flow. And then we start after two months to also really push and make it really fast.”

Plus, as in More

PluSport represents 12,000 members, many of whom are heavily disabled and only a small percentage of who compete on the track, in the pool, on the slopes, or in the gym in Paralympic competitions.

“Only a small part (of the organization’s mission) is Paralympic sport, where we’re trying to reach the best results in the highest competitions in the world,” Pfarrwaller says. “That’s maybe just a hundred athletes and we’re trying to bring them together with Olympic athletes from the Swiss Athletic Track & Field Federation.”

[av_button_big label=’Next post:’ description_pos=’below’ link=’manually, https://1080motion.com/recerational-volleyball-return-to-sport-protocols-patrick-marti/’ link_target=” icon_select=’no’ icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ custom_font=’#ffffff’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ color_hover=’theme-color-subtle’ custom_bg_hover=’#444444′ av_uid=’av-pu1hkj’]Bridging the Gap Between Elite and Recreational In Return to Sport Protocols[/av_button_big]

For his part, Pfarrwaller recently gave up the job as a teacher in a high school where he taught mathematics so that he could go from training his athletes part-time to having the bandwidth to train them on a full-time basis.

“Once we decided that our athletes can compete and go to a final or win medals, we realized they need professional training,” Pfarrwaller says. “And our aim now is that these athletes that I coach can train in an inclusive setting. For this step, however, we still need some patience and we have to win the trust of many coaches first.”